Today’s post is from guest blogger, Carrie Asselin, the sister of Nathaniel Asselin who tragically took his own life at age 24 after battling severe OCD and BDD (body dysmorphic disorder). In this post, Carrie writes about the experience of growing up with an older brother who was her hero and best friend, but who was also tormented by these disorders. Carrie now lives in Boston, MA, where she works in a lab that researches Alzheimer’s at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Today’s post is from guest blogger, Carrie Asselin, the sister of Nathaniel Asselin who tragically took his own life at age 24 after battling severe OCD and BDD (body dysmorphic disorder). In this post, Carrie writes about the experience of growing up with an older brother who was her hero and best friend, but who was also tormented by these disorders. Carrie now lives in Boston, MA, where she works in a lab that researches Alzheimer’s at Massachusetts General Hospital.

My story as the sibling of someone who suffered from Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) is a complicated one. My brother, Nathaniel, battled these disorders for 13 years before he made a decision to take his life in April 2011. As his only sibling, I have a unique perspective of what it was like to grow up alongside OCD and BDD.

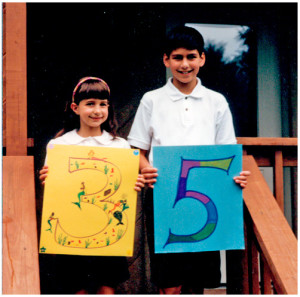

It began in 1998 when I was nine and Nathaniel was 11, and it happened practically overnight. His OCD took hold with a vengeance, and before we even had a clue what was going on, he was completely at the mercy of his compulsions. Even at such a young age, his biggest concerns were with body image (he was later diagnosed with BDD, a disorder related to OCD), and, for whatever reason, my physique became the standard to which he strived—and with my being over two years younger, he had a dangerous way to go to reach my weight. Along with refusing food, he began to copy my physical exertions, plus a little extra. If I ran across the yard, he would race after me, always a bit faster, a little farther. It was incredibly annoying to my 9-year old self, having my best friend and main companion suddenly turn my every action into a competition, and it was very difficult for me at first to recognize that he was not doing it intentionally.

As his symptoms worsened over the first few months, my confusion was exacerbated by the fact that we struggled to verbally communicate about his illness—he kept his anxiety very hidden from me, deeply ashamed at how bizarre he was acting. I think that, as the older one, and the one who saw himself as my leader and protector, Nathaniel really struggled to admit how much control the disorders had over him.

One day when we were playing together out in our yard, I happened to jump once. He mimicked my movement with a wry smile on his face, which irritated me greatly. I jumped again, and so did he, the smile remaining but his eyes betrayed his mounting inner panic. I realized in that moment how helpless he was, and it suddenly dawned on me the amount of power I held, something I had never possessed as the younger child. It was intoxicating, and all my pent up frustration at Nathaniel for suddenly getting so much attention, ruining our playtime, and essentially ceasing to be the brother I adored so much, now had an outlet. If he took out his anger on me, I would retaliate by provoking his compulsions, despising myself for it but unable to find another release.

My parents did their best to facilitate family discussion about it, but Nathaniel would often shut down. Because of his shame and embarrassment, I also came to believe that OCD was something that should be kept a secret, without even really knowing why. When a classmate of his asked why he had missed so much school, I simply replied that he was sick. “Like pneumonia?” the confused 5th grader asked. “Something like that,” I muttered, somehow scared to admit that it was really OCD.

Fortunately, that initial dark period did not last long—once he was medicated, his symptoms reduced dramatically for several years to come, and our relationship got back on track. He confessed years later how much he hated himself for copying me, but I was still far too ashamed to admit that I had taken advantage of that at times.

Nathaniel’s initial concealment of his illness set the precedent for our discussions (or lack therof) about his struggles for the rest of his life. He was eventually diagnosed with both OCD and BDD, and battled over the years with the recurrence of symptoms and depressive episodes. Despite all that he was going through, he remained a wonderful brother and my soul mate—he was incredibly supportive, and although my petty teenage issues paled in comparison to the severity of his, he always validated my feelings and offered the best advice. Our personalities were intertwined to the point that it was often hard to determine which character traits originally belonged to whom. Like me, Nathaniel was sensitive and highly observant of his surroundings, and we shared an identical sense of humor that was always building upon a massive repertoire of our own recurring jokes.

Over time, Nathaniel’s BDD symptoms put a real damper on his quality of life, but they still were not something that we talked about much. If he had a breakdown, my parents would step in to help while I often retreated from the area if I thought it would help minimize his stress — all the while, that feeling of helpless frustration came creeping back, leaving me to feel as if I was 9-years-old all over again. I found other ways to support him through it all, but watching the BDD take such a toll on him without being able to talk to him about it was unbearable at times. Since his death, I have wrestled strongly with my regret over not pushing him harder to share his struggles with me—but as many siblings of people with a chronic illness know, there comes a point when your brother or sister been ill for so much of your life, that you almost forget to wonder if it has to be that way.

Looking back, Nathaniel’s embarrassment over his own condition paralleled society’s views of psychiatric illness. Things have already come a long way since 1998, but the stigma over mental health issues still persists. And so the question remains: How can we create a society that is comfortable acknowledging and discussing psychiatric illness?

I believe the answer lies in awareness. When Nathaniel was first diagnosed, neither of us had ever heard of OCD or BDD. Had we been already familiar with these disorders, could that have helped him feel less odd? Would he have been more open to discussing it? Those with BDD often experience even more shame and self-disgust than those with OCD, resulting in much higher suicide rates. Can spreading awareness about the prevalence of these illnesses help combat some of that?

I think it absolutely can. It’s hard enough to have to come out as someone who struggles with OCD or BDD, without having to also give a psychology lesson about the disorders at the same time. With increased awareness comes a multitude of positive effects—reduced stigma, faster and more accurate diagnoses, more affected individuals seeking treatment sooner, and an increase in research activity to develop more effective treatments.

Last year, heartbroken over my brother’s death, my father started a pilgrimage to raise awareness about OCD and BDD, and to memorialize Nathaniel. He began walking from our home in Cheyney, PA, and eventually reached Boston, 6 weeks and over 500 miles later. The International OCD Foundation welcomed my Dad to Boston with a rally on June 7th, 2012, where my mom and I held the finish line tape for him to cross, signifying the end of his journey. But, it was not the end. My dad calculated that he walked over 1 million steps on his journey — 1 million steps towards OCD and BDD awareness, 1 million steps towards a better understanding of mental illness, and an end to such prevailing stigma — but he also remarked that we have many, many more to go before we get there.

To that end, this year the International OCD Foundation (IOCDF) is asking all of us to help walk another 1 Million+ Steps 4 OCD Awareness. For those in the Boston area, we will be walking together on June 8, 2013 at Jamaica Pond (click here for details). For those not located in Boston, we are asking you to walk with us “virtually,” by pledging to walk any amount of steps of steps towards the cause, and helping us raise awareness about OCD, and raising money for the IOCDF to help support their mission to help all individuals affected by OCD and related disorders to live full and productive lives (click here to learn about the virtual walk).

Please bring your families, friends, and coworkers, as we together walk 1 million steps (or more) towards finding relief for all of those individuals struggling with OCD and related disorders, and their families, many of whom have been suffering along with them.

To join, go to iocdf.org/1million4ocdwalk and click “I’m In” and register to either walk with me in Boston or register as a “virtual walker” to walk in your community. Then, help us spread the word about this walk, about this cause, and about why you want to help.

I will be walking in memory of Nathaniel on June 8th, 2013. I hope you will join me.

Leave a Reply